- Home

- Sam Moskowitz (ed)

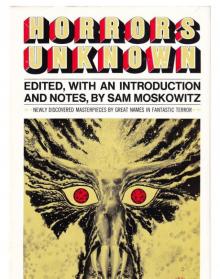

Horrors Unknown

Horrors Unknown Read online

First ePUB Edition

2012

Amontoth/Genesis

* * *

INTRODUCTION

* * *

The title of this book—Horrors Unknown—has a double meaning. It is, first, a collection of fine stories whose plots or approach to horror is so different, so unusual, so off-beat, as to present the reader with an element of novelty in the reading of the macabre which will almost seem to broaden the scope of the genre. Secondly, it offers an unparalleled assembly of previously unanthologized, and in many cases literally undiscovered, masterpieces of fantastic terror by authors so famous it seems almost incredible that so many works could have been overlooked.

The stories in this volume are of the type that the successful anthologist rations out at the rate of one, or at the most two, to a book. They are the occasional nuggets of rhetorical gold that the researcher pans out as the result of years of reading and collecting. They are rare and fugitive, and in addition to their individual merit they are virtually collector’s items—qualities they possess in common and the rationale of the double-entendre in the title Horrors Unknown.

The editor is a historian in the field of fantastic literature. Each year, several thousand books and magazines are added to a collection that expands from room to room. These volumes and periodicals are the tools and the target of research. Scholarship m modern times too frequently consists of accepting existing references as definitive or hardcover printings as the sum total of an author’s work. There is also the implied assumption that if something has never been reprinted it is not worth reprinting or if academic approval has not been forthcoming, the item cannot be of superior quality. Needless to say, the editor holds a different view. All stories in this volume were tracked down from their original sources of publication. At the time of collection, only one had ever appeared in an anthology before, either in or out of the fantasy field, and that one ninety years ago! After thirty-seven years of reading and collecting in the field, the editor did not feel he had to lean on someone else’s opinion to determine whether the stories were worth preserving.

Actually, it represented a sort of a challenge and a lark. With only the editor of Walker’s science fiction and fantasy series, Hans Stefan Santesson, an unregenerate fantasist and bibliophile if there ever was one, aware of my intention, I selected the stories for the following reasons.

“The Challenge from Beyond” brings to the fore an analogy with baseball and football fans, who take great delight in watching all-star games, exhibitions in which the most popular and outstanding competitors from an entire league are assembled to play together. While it is the dream team, it does not necessarily follow that they will play the greatest game of the year. A team, to be truly effective, must learn to function as a group, and a team of the greatest stars is no exception, but just the thrill of assembling them and watching them perform is an end in itself.

Through a series of special circumstances, a group of all-time great writers of fantasy came together to collaborate on a single story. The trick with these particular authors can never be repeated. Of the five involved, three are dead. The authors who wrote it round-robin style were C. L. Moore, A. Merritt, H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, and Frank Belknap Long, Jr. Long dead are A. Merritt, once-in-a-lifetime author of such masterpieces as The Moon Pool, The Ship of Ishtar, and Dwellers in a Mirage; H. P. Lovecraft, who has already become a legend with his fame expanding each year; and Robert E. Howard, whose fabulous barbarian Conan has become a literary landmark. Still alive are C. L. Moore, creator of Northwest Smith and Jirel of Joiry, and Frank Belknap Long, Jr., a close friend and literary bedfellow of H.P. Lovecraft.

Between the years 1940 and 1960, Edison Marshall was considered one of our finest writers of historical romances. Tyrone Power and Kirk Douglas were among the stars featured in moving picture adaptations of his works, and every paperback store features his books. Long before he had gained such recognition, he was a fine fantasy writer. “The Flying Lion” is an unacclaimed masterpiece of horror, and may also prove a revelation to the followers of Edgar Rice Burroughs, who probably have overlooked it in their collecting of Tarzan-related stories.

Frank Norris, who died tragically young of a burst appendix, was on his way to becoming one of America’s great literary figures with his trend-setting novels of naturalism, The Octopus and The Pit. He is never thought of as one of the important writers of horror and the supernatural. “Grettir at Thorhall-siead,” never as much as mentioned in scholarly books on occult literature, should prove a bombshell to the academics as well as the cognoscenti.

The publication of “Shambleau” in the November, 1933 Weird Tales, with its steely-eyed interplanetary mystic adventurer Northwest Smith, created an overnight reputation for C. L. Moore. The promise displayed in that first story was amply vindicated, but despite her literary successes the character of Northwest Smith has remained paramount in the thoughts of her followers, though she has written no new story in the series for over thirty years. However, one work was never professionally published, and appeared in a mimeographed magazine in 1938 with a circulation of sixty copies. That story was “Werewoman.” Unlike the others, it is a supernatural fantasy and not a science fantasy, and its printing here is its first truly professional appearance.

Fitz-James O’Brien was probably the finest American short story writer of the strange and unknown in the period between Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce, his landmarks “The Diamond Lens” and “What Was It?” being favorably evaluated in any definitive discussion of American literature. For the first time in ninety years, one of his most striking, surrealistic novelettes, “From Hand To Mouth,” is brought back into print, an event not only for his followers but for students of the short story.

There have been a number of occult detectives in British and American literature since the turn of the century, but by odds the most popular was Jules de Grandin, creation of Seabury Quinn in the pages of Weird Tales. “Body and Soul” epitomizes the best elements in the series and has never been reprinted since its first appearance forty-two years ago.

The pen name of Francis Stevens hid the identity of Gertrude Bennett, acknowledged by such masters as H. P. Lovecraft and A. Merritt as one of the finest writers the fantasy field ever produced. Her entire production of a handful of novels and short stories, all of them fantastic either in theme or presentation, was believed accounted for until the discovery of “Unseen—Unfeared,” never previously listed in a bibliography, let alone reprinted.

Ray Bradbury is today acknowledged as one of the finest of all modern writers of horror. His first story, “Pendulum,” written in collaboration with Henry Hasse, has never been included in hard covers. As an intriguing comparison, the first version of the story written entirely on his own and published in his amateur magazine Futuria Fantasia is also reprinted so that the differences between it and the final collaboration can be evaluated. This dual presentation is of historical importance to those interested in studying the development of Ray Bradbury as an author.

To the literary world Edwin L. Sabin is one of the most respected writers of historical adventure concerning the old West. To fantasy lovers, his lost-race novel The City of the Sun has served as credentials for his ability in their specialty. However, in the short story field, “The Devil of Picuris,” never reprinted since its original publication, offers an even more effective testimony to his effectiveness in this media.

For something like thirty-one years, A. Merritt worked in various editorial capacities on the American Weekly, which at one time claimed the largest circulation of any publication in the world. It has long been conjectured as to whether or not he wrote an identifiable piece of fiction for them during that period. A sear

ch has brought to light a short story, “The Pool of the Stone God,” credited to one W. Fenimore, which, from internal evidence would seem very likely to be Merritt’s work. It is presented here for the readers to evaluate.

The foregoing comprise the contents of an anthology we believe to be unique of its kind. Each story is prefaced by comprehensive background notes which embody a great deal of special research, much of it revealed for the first time in the pages of this book. What the editor has tried to do is take the readers along with him on a voyage of discovery of lost and almost forgotten masterpieces, so they could experience the thrill of the search as well as the reward in the reading.

* * *

THE CHALLENGE FROM BEYOND by C. L MOORE,

A. MERRITT, H. P. LOVECRAFT, ROBERT E. HOWARD, and FRANK BELKNAP LONG, JR.

* * *

This utterly remarkable round-robin science fantasy is a one-of-a-kind that owes its creation to an unusual set of circumstances which probably could not be duplicated with a contemporary group of authors of equal stature. It first appeared in the September, 1935 issue of Fantasy Magazine, one of the earliest and perhaps still the greatest science fiction and fantasy fan magazine ever published.

The publication wanted something truly outstanding for its third anniversary issue, so its editor, Julius Schwartz, struck upon the idea of two round-robin stories, one of science fiction and the other of fantasy, to be written by the greatest living writers that would cooperate. The magazine had a precedent for scouring such cooperation. Beginning with its July, 1933 issue (then titled Science Fiction Digest), they published as a serial supplement to the magazine a novel titled Cosmos, written by sixteen authors and issued in eighteen segments. As each author completed a chapter, the next took up from where the other had broken off. The individual chapters had to be complete in themselves, yet carry the novel forward. The authors contributed their efforts gratis to make this novel concept a reality.

“The Challenge from Beyond” was secured the same way, with the difference that each contribution was much shorter in scope than those of Cosmos, and rather than being complete in itself would leave a ticklish situation for the next author to extricate himself from. There was a science fiction story also titled “The Challenge from Beyond,” which was written cooperatively by Stanley G. Weinbaum, Donald Wandrei, Edward E. Smith, Harl Vincent, and Murray Leinster; it appeared side-by-side in the September, 1935 Fantasy Magazine with the fantasy portion printed here.

All the authors included at the time were “hot then, and most of them have climbed into the category of producers of classics for the genre since that time.

C. L. Moore was acknowledged to be a great discovery upon the publication of her first story, “Shambleu,” in the November, 1933 Weird Tales, with its sensual presentation of a Medusa-like girl in a Martian setting, and its introduction of Northwest Smith. Her reputation was enhanced by a new series introducing the heroine Jirel of Joiry shortly afterward, and solidified further with the presentation of a number of poetic space fantasies in Astounding Stories.

A. Merritt had long been a fixed star in the field, with permanent classics including The Moon Pool, The Metal Monster, The Ship of Ishtar, Dwellers in a Mirage and serialized only the year previous in Argosy, Creep, Shadow! No one, least of all himself, was aware at the time that his last major work had been completed and with his assumption of full editorship of American Weekly in 1937, the opportunities for creative authorship would end.

H. P. Lovecraft, revered by the readers of Weird Tales for such unique masterpieces as “The Rats in the Walls,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness,” living in genteel poverty, would be dead of Bright’s disease within eighteen months of publication of the story, with recognition never dreamed of, even by his active imagination, yet to come.

An even shorter skein on the thread of life was the destiny of Robert E. Howard, who on June 1 1, 1936, would end it all at the age of thirty, while still climbing towards the peak of his career. His character of Conan would become an influence treating the entire field of sword and sorcery which exists today, and the vigor and color of his writing method were to be copied by an entire school of fantasy writers.

Frank Belknap Long, Jr., a confidant of H. P. Lovecraft, enjoyed his greatest reputation because he had set many of his stories into a framework, mythology and cosmos similar to that of the Cthulhu series—such stories as “The Space Eaters,” “The Hounds of Tindalos,” and “The Horror from the Hills”—but had moved into other areas of science fiction and fantasy with a rich, rhythmic writing style which distinguished him from his contemporaries.

The longest portion of the story, about 2,500 words, was written by H. P. Lovecraft, and was presented as a complete story in the May, 1960 issue of Fantastic Science Fiction Stories. Probably the finest writing in the story is Frank Belknap Long’s poetically done conclusion.

The collaboration was reprinted complete in the H.P. Lovecraft collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep, published by Arkham House, 1943, a volume of such rarity and high cost today that it is off-bounds to most readers. Both the science fiction and the fantasy versions of “The Challenge from Beyond” were reprinted as separate mimeographed pamphlets by William Evans and distributed through The Fantasy Amateur Press Association in February, 1954. Since that association has only sixty-five members, copies are even more rare than Beyond the Wall of Sleep.

The original printing of the stories in Fantasy Magazine was only two hundred copies, of which about twenty or so were run off on coated stock for presentation to the authors and the editors, and the rest appeared on pulp paper.

The appearance of “The Challenge from Beyond” here marks its first availability outside of a limited edition and the first time it has ever been included in an anthology of the fantastic.

* * *

THE CHALLENGE

FROM BEYOND

* * *

by

C. L. MOORE,

A. MERRITT,

H. P. LOVECRAFT,

ROBERT E. HOWARD,

and FRANK BELKNAP LONG, JR.

I / C. L. MOORE

George Campbell opened sleep-fogged eyes upon darkness and lay gazing out of the tent flap upon the pale August night for some minutes before he roused enough even to wonder what had wakened him. There was in the keen, clear air of these Canadian woods a soporific as potent as any drug. Campbell lay quiet for a moment, sinking slowly back into the delicious borderlands of sleep, conscious of an exquisite weariness, an unaccustomed sense of muscles well used, and relaxed now into perfect ease.

These were vacation’s most delightful moments, after all—rest, after toil, in the clear, sweet forest night.

Luxuriously, as his mind sank backward into oblivion, he assured himself once more that three long months of freedom lay before him—freedom from cities and monotony, freedom from pedagogy and the University and students with no rudiments of interest in the geology he earned his daily bread by dinning into their obdurate ears. Freedom from—

Abruptly the delightful somnolence crashed about him. Somewhere outside the sound of tin shrieking across tin slashed into his peace. George Campbell sat up jerkily and reached for his flashlight. Then he laughed and put it down again, straining his eyes through the midnight gloom outside where among the tumbling cans of his supplies a dark anonymous little night beast was prowling. He stretched out a long arm and groped about among the rocks at the tent door for a missile. His fingers closed on a large stone, and he drew back his hand to throw.

But he never threw it. It was such a queer thing he had come upon in the dark. Square, crystal-smooth, obviously artificial, with dull rounded corners. The strangeness of its rock surfaces to his fingers was so remarkable that he reached again for his flashlight and turned its rays upon the thing he held.

All sleepiness left him as he saw what it was he had picked up in his idle groping. It was clear as rock crystal, this queer, smooth cube. Quartz, unquestionably, but

not in its usual hexagonal crystallized form. Somehow—he could not guess the method—it had been wrought into a perfect cube, about four inches in measurement over each worn face. For it was incredibly worn. The hard, hard crystal was rounded now until its corners were almost gone and the thing was beginning to assume the outlines of a sphere. Ages and ages of wearing, years almost beyond counting, must have passed over this strange clear thing.

But the most curious thing of all was that shape he could make out dimly in the heart of the crystal. For imbedded in its center lay a little disc of a pale and nameless substance with characters incised deep upon its quartz-enclosed surface. Wedge-shaped characters, faintly reminiscent of cuneiform writing.

George Campbell wrinkled his brows and bent closer above the little enigma in his hands, puzzling helplessly. How could such a thing as this have imbedded in pure rock crystal? Remotely a memory floated through his mind of ancient legends that called quartz crystals ice which had frozen too hard to melt again. Ice—and wedge-shaped cuneiforms—yes, didn’t that sort of writing originate among the Sumarians who came down from the north in history’s remotest beginnings to settle in the primitive Mesopotamian valley? Then hard sense regained control and he laughed. Quartz, of course, was formed in the earliest of earth’s geological periods, when there was nothing anywhere but heat and heaving rock. Ice had not come for tens of millions of years after this thing must have been formed.

And yet—that writing. Man made, surely, although its characters were unfamiliar save in their faint hinting at cuneiform shapes. Or could there, in a Paleozoic world, have been things with a written language who might have graven these cryptic wedges upon the quartz-enveloped disc he held? Or—might a thing like this have fallen meteor-like out of space into the unformed rock of a still molten world? Could it—

Horrors Unknown

Horrors Unknown